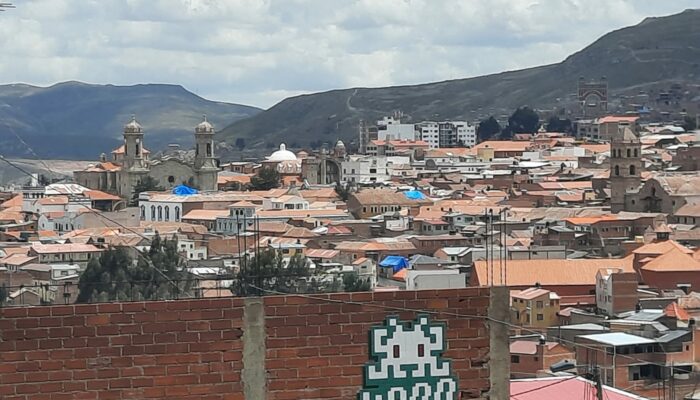

Although the city of Potosí lies at an altitude of 4,070 m, making it one of the highest cities in the world, this is nothing compared to the Cerro Rico mountain, which majestically dominates the city.

This Andean peak, which rises to 4,782m south of Potosí, is both a symbol of wealth and distress for those who walk on it, but what does it really hide? Centuries of history inhabit its land and take shelter in its natural resources. Still known today for its major mining dramas, it has been listed as a World Heritage Site in Danger by UNESCO since 2014.

It would be a shame not to see the mountain and the city during your trip to Bolivia, so between splendour and decadence, Thaki Voyage invites you to dive into this Bolivian treasure, which has a lot to offer.

Cerro Rico, the story of the mountain's riches

Since the 16th century, Cerro Rico has been exploited for its many mineral resources, but it is above all thanks to its silver soil that the mountain has gained its reputation. This abundance of silver earned it several names, including the one we currently use in Spanish, el Cerro Rico: translated here as “the Rich Mountain”, which is a direct reference to the resources found and exploited by the conquistadors.

In fact, the mines were discovered in 1545 under Spanish rule, marking the beginning of the mining history of this famous mountain. Diego Huallpa, an Indian slave, discovered the first veins of silver in January of that year.

The new mine became a magnet for the Viceroyalty of Peru, and in 1546 the town of Potosí was founded at the foot of the Cerro Rico’s intense activity. The city became known as the “Imperial City”, and it was only natural that the Spaniards should take possession of this area and the Cerro Rico to finance the affairs of the Spanish Empire. Potosí and its mountain became one of the main economic sources of the old continent.

The motto “I am the rich Potosí, treasure of the world… coveted by kings” illustrates the situation at the time. Nevertheless, before the arrival of the colonists, legend has it that the locals were aware of the mountain’s wealth, without exploiting it: the concerns of the inhabitants of the time were far removed from those of the Spanish conquistadors.

In pre-Columbian times, the mountain was a sacred place for the local population, who considered it a huaca, a site dedicated to the admiration of the Amerindian divinity. Sacrifices and rites were performed there in honour of the god Huiracocha or the Pachamama.

In Quechua, Cerro Rico is called Huayena Potosí, which means “the one who explodes”, in direct reference to the powers of the deity Huiracocha, who was very important in Inca cosmogony.

Miners, mines and the devil: meeting the famous Tío of Cerro Rico

Today, the site is still being mined, with the risk of collapse becoming ever greater. What’s more, the conditions in which the workers labour remain particularly trying and extreme, which is why the miners always ask for El Tío’s appeasement and benevolence before starting their day’s work.

The men pray to him to protect those who venture into the mountain’s dark, narrow tunnels. According to popular belief, El Tío or El Supay is the god of the underworld.

His features are those of an imp, and the miners make offerings to him, including cigarettes, alcohol and coca leaves, which they themselves chew to withstand the hardships of their work. This is reminiscent of the offerings made to El Ekeko (see our January article), but the world in which these men work is akin to hell, and El Tío has nothing to do with the cheerful figure of Ekeko. The reference to the devil is obvious, as they believe that the earth they dig belongs to him.

The meeting of indigenous and Spanish beliefs can also be found at the heart of the mine, since the cult of Tío was born at the very heart of the Cerro Rico. Tío (uncle) is thought to be a distortion of the word Dios (god).

His statuette can be found in several of the mountain’s galleries, as the Cerro Rico has more than 600 gallery entrances for around 200 mines.

This extensive mining operation explains the many accidents that occur today.

Potosi: a brief history

Once billed as the largest city in the world, Potosí enjoyed great economic prosperity, which has since come to an end. Despite this decline, the city’s churches, colonial buildings and pedestrian streets have all been preserved.

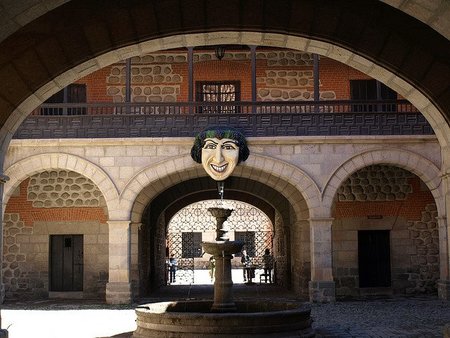

Its historic centre is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, so a visit to its 22 churches is a must, including the rock-hewn church of San Francisco, the church of San Lorenzo and the cathedral. The Torre de la Compañia de Jesús is a must-see, as is the Casa Nacional de Moneda, considered to be the city’s most famous museum.

You can also explore the old workers’ quarters, known as barrios mitayos like the noble quarters, because the division of quarters between the colonists and the forced labourers was really visible in Potosí. In fact, only a man-made river separated these two areas.

Local Baroque and Indian influences have made the city one of Bolivia’s leading architectural centres. The Andean Baroque style makes it an authentic testimony to the mining history of the Americas.

It’s best to visit Cerro Rico and the town of Potosí between April and October!

The panoramic views from the mountain are breathtaking, but visiting Potosí is far from a trivial experience. A former industrial complex on a global scale, the city will touch you and have an impact on your journey.

This is another side of Bolivia that Thaki Voyage invites you to glimpse, up there on the mountain, to rethink the history of this country!

Mathilde Leroux